When asked what comes to mind when they think of psychotherapy, the most common answer people give is some variation of the following: A person lying on a couch talking about their earliest memories while a mostly silent figure takes notes. This image of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic method has been burned into our schemas and colors our conceptualization of clinical psychology despite the fact that it bears little resemblance to the method of most modern practitioners. In fact, those who still strictly adhere to the tenets of Freudian thought are often met with resistance and outright contempt by others in the field. Yet the image persists. As a result of a

recent film by Canadian director David Cronenberg, discussion of this controversial practice has reached outside of the psychological community.

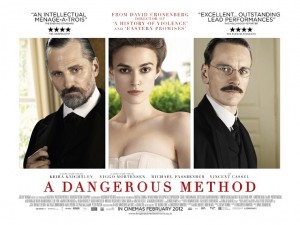

A Dangerous Method was released last fall to mostly positive reviews from critics and signals a substantial departure from the director’s usual fare. The film, which is ultimately a historical biography, follows his two searing, Oscar-nominated forays into dark and violent underworlds that our hidden in our midst (A History of Violence and Eastern Promises). Based on the 1993 nonfiction book by John Kerr entitled A Most Dangerous Method: The Story of Jung, Freud, and Sabrina Spielrein, the film chronicles the early days of psychoanalysis. As the book’s title clearly states, its focus is on the interrelationships of three characters – two the founding fathers of psychology and the woman whose contribution to the field has been relegated to obscurity (as have those of far too many women). Sigmund Freud, the Austrian neurologist who is credited with the development of psychoanalysis, is played by Viggo Mortensen in a delightfully against-type performance. Carl Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist who is credited with the founding of analytical psychology, is played perfectly by rising star Michael Fassbender. Sabina Spielrein, the Russian physician who was one of the first female psychoanalysts and (interestingly enough) counted legendary developmental psychologist Jean Piaget among her patients, is played by Keira Knightly, in a performance that is highly problematic.

Although it was noble of Kerr and screenwriter Christopher Hampton to give Dr. Spielrein credit for her influential role in the early days of psychoanalysis, there is a strong undercurrent of sexism in her portrayal that is disconcerting. We first encounter Spielrein as a woman being treated for hysteria, the condition for which psychoanalysis was originally specifically targeted at, yet curiously does not seem to exist any more – at least in the over-the-top form with which it was described. Although perhaps true to historical accounts, Knightley’s braying and twitching interpretation of the young woman is so overdone that it is cringe inducing. She undergoes psychoanalysis from Jung, who has just learned of Freud’s new practice, and he inexplicably cures her by helping her realize that she used to get sexually aroused when her father would beat her and that she has done nothing to deserve such a punishment. The revelation is a quick and unconvincing development. She manages to overcome her illness and becomes a brilliant academic and clinician, despite the fact that Jung adopts her work and fails to give her credit. Unfortunately, the filmmakers seem less interested in Spielrein’s intellect and more in her red hot passion. They focus on the fact that she likes to have kinky sex with Jung because it reminds her of her beatings and that once spurned she will wield a knife better than Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction. Eventually Spielrein left both men behind to start a family and work as a physician, only to be executed along with her young children by the Nazis in World War II. Her memory deserves better than this portrayal of grotesque insanity, sexual submission, and seething jealousy.

Given the problems with Spielrein’s portrayal, it is unsurprising that the best scenes in the film are those between Jung and Freud. After a lengthy correspondence, the two finally meet and speak for over 13 uninterrupted hours. They explore and debate the tenants of Freudian psychoanalysis, which include: 1) human behavior, experience, and cognition are largely determined by irrational drives, 2) these drives are largely unconscious, 3) attempts to bring these drives into awareness are met with psychological resistance in the forms of defense mechanisms, 4) one’s development is primarily determined by events in early childhood, 5) conflicts between the conscious and unconscious result in mental disturbances, such as neuroticism, anxiety, and depression, and 6) liberation from the effects of the unconscious is achieved by bringing the material into consciousness. Jung is skeptical of the approach’s basis in clinical observation (as opposed to empirical evidence) and its relentless obsession with sexuality as the driving force behind, well, everything. Despite his obsession with sexual themes, Freud was against having sex with patients, acknowledging that such passion is the result of transference (the unconscious redirection of feelings from others in one’s life toward another) and results in an unhealthy power differential. Nevertheless, Jung engages in a sexual relationship with Spielrein, hastening their perhaps inevitable falling out.

The falling out between Jung and Freud is about more than just sex, however. Jung became interested in the supernatural, which influenced the development of his theories of symbolism, archetypes, and transformation. The time leading up to the publication of Jung’s The Psychology of the Unconscious (1916), in which Jung posed a theory of the libido that markedly diverged from Freud and thus cemented their falling out, is detailed in the film. As is the case with many historical films, A Dangerous Method suffers from a tendency to play more as a series of staged events than it does an actual narrative. Most of the scenes are brief and given little room to breathe, which the subject matter here necessitates. It covers three historical figures over several years and barely clocks in at 95 minutes. Yes, the production values are top notch, but this is a film about intellect not style. The film would have benefitted from exploring less of the ideological warfare between the two men and more on how and why their schools of thought managed to influence the practice and perception of mental health treatment over the next century.

Increasingly, the field of clinical psychology is moving toward a model of evidence based practice, in which the modality with which a client should be treated is selected based on whether there is data supporting its efficacy for the population and presenting problem at hand. This has led to a widespread adoption of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a modality that is based in short term, problem-focused strategies that are derived from the science and theory of learning and cognition and are aimed at modifying the maladaptive thinking patterns and behaviors that are believed to lead to the maintenance of psychological suffering. A preponderance of evidence exists for the effectiveness of CBT at targeting a number of psychological disorders, including (but not limited to) anxiety, depression, substance use, and eating disorders. As this evidence has amassed over the past five decades, the percentage of clinicians who see CBT as their primary theoretical orientation has increased from 8% in 1960 to 46% in 2010 (Norcross & Karpiak, 2012).

During the same period, percentages of clinicians who see psychoanalysis as their primary theoretical orientation fell substantially from 35% in 1960 to 18% in 2010. However, it is still highly prevalent. With nearly 1 in 5 clinicians considering themselves to be influenced by the Freudian school of thought. Critics of this group (which are typically, but not always, proponents of CBT) argue that psychoanalysis is “a dangerous method” due to the fact that the key tenets of the theories of psychoanalysis are fundamentally untestable and that it is unethical to administer an intensive and costly treatment with limited empirical evidence when more targeted, cost effective approaches are available.

Although they make compelling arguments, theirs is a bit of a straw man argument. Although there are a select few out there who still practice classic Freudian psychoanalysis by seeing clients 5 times a week, having them recount early memories of their childhood while lying on a couch, and providing guidance through interpretations of free word associations, dreams, and other content, the majority practice one of the many types of psychodynamic therapies that evolved considerably since the days of Freud. Such psychodynamic therapies still consider the conflict between unconscious and conscious material and issues of transference and countertransference in the therapist-client relationship, but usually are less intensive (with weekly sessions, similarly to CBT), take a much greater interest in present functioning, and feature a far more collaborative therapeutic relationship than traditional practices. Interestingly, the image of Freudian psychoanalysis has been so deeply entrenched in our schemas that even those in the field have trouble seeing past it.

As a clinician in training, I am not firmly positioned in either camp. I am passionate about treatment that is targeted, ethical, and scientifically and theoretically sound, but I also acknowledge that many individuals desire – and do benefit from – the exploration of the past. I also believe that for many individuals, the relationship between the therapist and the client can have a healing effect on the client’s suffering and serve as a basis for objective behavioral change. However, to me the most interesting question is not who is right in the war being raged between the analysts and the behaviorists, but rather what the effect of this enduring and pervasive image of our field has wrought. I fear that it continues to support the image that clinical psychology is a pseudo-science that is overwhelmingly preoccupied with sex, desperately seeks catharsis by exposing the pain of client’s childhoods, and is practiced by wise clinicians who have the power to correctly interpret one’s thoughts, feelings, and actions. Such an image is not one that elicits great respect – either from the suffering who could benefit from psychological services or the policymakers who decide how money gets spent and thus how access to services gets granted or denied. Insofar that it maintains this problematic and inaccurate image, theschoolof Freudian psychoanalysis is a dangerous method indeed.

[This is the fourth article in Richard’s series on psychology and film. The previous articles can be found below. More will come this summer.

- Recent Film Provides Insight into the Terror and Complexity of Prodromal Schizophrenia — March 28, 2012

- Hauntingly Accurate Portrayals of Severe Mental Illness at a Theater Near You— December 12, 2011

- New Movie Portrays Cancer Perceptively but Psychology Offensively — October 24, 2011]