This post is the first of three on the Wason selection task (Part II), and part of our ongoing series exploring classic experiments and theories in the history of psychological research.

In the 1960s, Peter Cathcart Wason introduced a test of logical reasoning that he termed the selection task (1966, 1968, 1969a, 1969b). Almost fifty years later, the Wason selection task is still a source of much research and debate, albeit not quite in the way he had originally intended. Introduced as a test of his theory of confirmation bias, Wason’s task has ended up a widely used experimental paradigm for examining human reasoning in the domains of abstract logic, social conduct, and various other semantic contexts. The task has become contentious in cognitive science research, but it is still commonly studied today due to the fact that people’s performance demonstrates a striking content effect, although the psychological account of when and how this phenomenon occurs has been continually revised over the last few decades. Before going any further, let’s try Wason’s original version (1966):

Problem 1

You are shown these four green cards and given the following prompt:

You are told these four cards have a letter on one side and a number on the other. You are given a rule about the four cards: If a card has a vowel on one side, then it has an even number on the other side. You are asked, which card(s) do you need to turn over in order to determine if the rule is true or false?

[expand title=”Click here to show typical results for this experiment.”]

This abstract form of the Wason selection task generally yields the following distribution of answers (Wason & Shapiro, 1971):

~ 45% pick the A card and the 4 card

~ 35% pick the A card alone

~ 7% pick the A card, 4 card, and the 7 card

~ 4% pick the A card and the 7 card [correct]

~ 9% pick other combinations of cards

[/expand]

The shocking thing about Wason’s results is that the logically correct (normative) answer is only chosen by about 4% of subjects (Wason & Shapiro, 1971). Although subjects clearly recognize the importance of selecting the A card, it is logical to select the 7 card as well, because in the event that it has a vowel on the other side, the rule would be violated (thus falsified). Conversely, there is no logical reason to select the 4 card because it is not possible for it to falsify the rule––whether there is a vowel or a consonant on the other side is irrelevant as there is no restriction on an even-consonant pair.

A bit of logic

In order to more precisely characterize subjects’ logical reasoning, it’s worthwhile to summarize a few bits of formal logic. First, the logical structure intended in Wason selection tasks is a simple conditional––that is, an “if P then Q” statement. When it comes to the logical form of a conditional, P → Q, we call proposition P the antecedent and proposition Q the consequent (the thing that follows from the antecedent). We can either affirm (state as true) or deny (state as false) either of the propositions, thus there are four simple argument structures that could be applied. Two of these arguments are logically valid (their conclusion will always be true if their premises are true), and the other two are logically invalid (their conclusion can be false even if their premises are true).

Table 1: Valid and Invalid Arguments for Conditional Logic

Affirming the Antecedent (modus ponens)

1. P → Q

2. P

3. Q

Denying the Consequent (modus tollens)

1. P → Q

2. ~Q

3. ~P

Affirming the Consequent (INVALID)

1. P → Q

2. Q

3. P

Denying the Antecedent (INVALID)

1. P → Q

2. ~P

3. ~Q

Table 1 shows the four simple arguments for P → Q, with their conclusions below the lines. The more obvious of the valid arguments is Affirming the Antecedent, which is called modus ponens. Clearly, if the premise P → Q is true, and we know P is true, then it follows that Q is true. The much trickier valid argument, which is most relevant to the effects we see in the Wason selection task, is Denying the Consequent (modus tollens). If we know that Q follows from P, but we know Q is false, then working backwards, P must also be false (or else Q would have been true). The validity of this argument becomes more apparent when we (validly) rearrange the conditional into its contrapositive form: ~Q → ~P, at which point we can use modus ponens to conclude ~P from ~Q (where ~X is read “not X“).

Wason’s subjects overwhelmingly failed to apply modus tollens, an important method of falsification. In order to fully assess whether the rule is true or false, one must look for the presence of P when there is an absence of Q, because the contrapositive requires there be no P if there is no Q. A simpler way to put this is that the only possible way to falsify the rule is to find a card with P on one side and ~Q on the other side; thus, only cards showing a P or ~Q are worth checking.

The content effect

In 1971, Wason and his doctoral student, Diana Shapiro, published a study demonstrating that participants still struggled with the abstract form of the task (even after being given a practice abstract problem to learn from). However, they were much more likely to give the modus tollens (~Q) response on an isomorphic thematic (semantic) version of the task. Subjects evaluated the rule “Every time I go to Manchester I travel by car,” using cards with cities on one side and modes of transport on the other. The explanation for the improved performance was that while the British participants wouldn’t have experience reasoning about relations between even numbers and vowels, they would have experience with traveling by car or train to cities in the UK, which facilitated their reasoning.

Because the two problems were written such that underlying logical structure was (presumably) equivalent across conditions, Wason and Shapiro (1971) argued that the improved performance on the thematic version was evidence of a semantic, not syntactic, effect. However, this in and of itself was not all that surprising––they acknowledged that the increased salience of ‘concrete’ terms, in line with prior research, might make them easier to symbolically manipulate and reason about. In a similar thematic experiment, Wason’s former student, Philip Johnson-Laird, along with Italian psychologists Paolo and Maria Legrenzi, (1972) tested British subjects on a form of the selection task using a rule about the value of postage stamps necessary to send a letter in a closed or open envelope (there was a lower postage rate for unsealed mail). Again, researchers believed that familiarity with the problem context helped them identify and reason normatively about the underlying logical structure, thus increasing the modus tollens responses.

Over the next decade came a series of seemingly contradictory results, such as Griggs and Cox’s (1982) failure to replicate Wason and Shapiro’s (1971) and Johnson-Laird et al.’s (1972) results using the same problem contexts (travel and postage) with American subjects. Golding (1981) used a similar postage rule that had actually been used in Britain (but had since been abandoned) and showed facilitation in older British subjects (who would have had experience with the old rule), but not younger subjects. Taken altogether, these results indicated an important role of prior experience with the content of a rule, especially instances of counterexamples (P & ~Q), leading some researchers to posit that reasoners typically don’t use general rules of inference, but rather draw from domain-specific memories of relevant counterexamples (Griggs & Cox, 1982; Manktelow & Evans, 1979). This so-called “memory-cueing” hypothesis stated that rather than facilitating the normative logical structure, domain-specific familiarity merely allowed participants to access their memory of counterexamples, obviating the need for domain-general logic.

Here is a classic example of a concrete Wason selection task with a rule most Americans should be familiar with (adapted from Griggs & Cox, 1982):

Problem 2

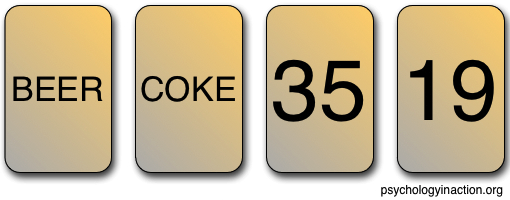

You are shown these four orange cards and given the following prompt:

You are told these four cards represent patrons in a bar, and each card has their drink on one side and their age in years on the other. You are given a rule about the four patrons: If a patron is drinking a beer, then they must be 21 years or older. You are asked, which card(s) do you need to turn over in order to determine if the rule is being followed?

[expand title=”Click here to show typical results for this experiment.”]

This permission-schema (alcohol) form of the Wason selection task generally yields the following distribution of answers (Griggs & Cox, 1982, Exp. 3):

~ 0% pick the BEER card and the 35 card

~ 20% pick the BEER card alone

~ 3% pick the BEER card, 35 card, and the 19 card

~ 72% pick the BEER card and the 19 card [correct]

~ 5% pick other combinations of cards

[/expand]

It seems unsurprising that people would understand that in this bar context, one would need to check a 19-year-old to make sure they weren’t drinking. It’s likely that subjects are familiar with the concept of alcohol laws and underaged drinking, and would readily recognize that a 19-year-old could potentially violate the rule whereas a 35-year-old could not. This is an instance in which subjects readily reason by modus tollens, because the contrapositive of the rule (“If you are NOT 21 years or older, then you must NOT be drinking beer”) seems much more obvious than the contrapositive in the abstract case (and certain other thematic domains). One reason for this difference is that subjects would not have personal experience with, for example, the abstract vowel-even number context from Problem 1, such that subjects would not be able to pull up a relevant memory to arrive at the normatively logical solution.

But the memory-cueing theory would not last long, because it was soon found that performance could be facilitated in contexts for which most people would not have had specific experience (e.g., a certain system of monitoring sales receipts in a department store; D’Andrade, 1982). Reasoners seem to be able to draw on some sort of more general knowledge––more abstract than specific memories but less abstract than formal logic.

In the next post on the Wason selection task, I will discuss the two popular theories that emerged in the 1980s and generated a new wave of interest in research with the task. Stay tuned for more!

References

D’Andrade, R. (1982, April). Reason versus logic. Paper presented at the Symposium on the Ecology of Cognition: Biological, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives, Greensboro, NC.

Golding, E. (1981). The effect of past experience on problem solving. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the British Psychological Society, Surrey University.

Griggs, R. A., & Cox, J. R. (1982). The elusive thematic-materials effect in Wason’s selection task. British Journal of Psychology, 73, 407–420.

Johnson-Laird, P., Legrenzi, P., & Legrenzi, M. S. (1972). Reasoning and a sense of reality. British Journal of Psychology, 63(3), 395–400.

Manktelow, K. I., & Evans, J. St. B. T. (1979). Facilitation of reasoning by realism: Effect or non-effect? British Journal of Psychology, 70, 477–488.

Wason, P. C. (1966). Reasoning. In B. Foss (Ed.), New horizons in psychology (pp. 135–151). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Wason, P. C. (1968). Reasoning about a rule. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 20, 273–281.

Wason, P. C. (1969a). Structural simplicity and psychological complexity: Some thoughts on a novel problem. Bulletin of the British Psychological Society, 22, 281–284.

Wason, P. C. (1969b). Regression in reasoning? British Journal of Psychology, 60, 471–480.

Wason, P. C., & Shapiro, D. (1971). Natural and contrived experience in a reasoning problem. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 23, 63–71.