[Warning: The following article contains spoilers. If you have not seen the film and do not wish to have key plot points and character dynamics revealed, do not proceed further.]

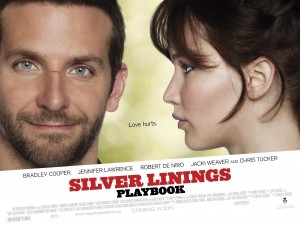

As discussed in all of my previous posts, dramatizing mental illness and mental health treatment is a risky pursuit. Sometimes the resulting product richly moves and informs, while other times it exploits and misleads. Perhaps an even riskier venture than dramatizing this topic is milking it for laughs. However, director David O. Russell decided he was up to the challenge, bringing his adaptation of Matthew Quick’s novel Silver Linings Playbook to the big screen this past November. The film mixes elements of several genres, but is ultimately a romantic comedy about a man with bipolar disorder and a woman with borderline personality disorder. The result has been a huge hit with every key sector. The Hollywood elite just rewarded it with 8 Oscar nominations and gave it the distinction of being the first film in 31 years (since Reds, Warren Beatty’s epic about Russian communism) to receive an Oscar nomination in every major category (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay, and all four acting categories). Critics have been kind as well, heralding the film as one of the best of the year. Audiences, too, have been enthused. The film has already earned nearly $80 million at the global box office (which is an enormous profit for a film that only cost $21 million to produce). There seems to be consensus that Silver Linings Playbook is a great film. But how does it fare as a portrayal of mental illness?

The film centers on Pat Jr., a Philadelphia native who at the beginning of the film is sprung from a residential treatment facility by his mother. We learn that he has been in an inpatient mental health facility for 8 months following a violent episode in which he attacked the man he caught his wife sleeping with. We are informed that he has a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and are given hints that while this was his first (or at least the worst) manic episode, Pat Jr. had brewing emotional and behavioral problems prior to it. Bipolar disorder is a mood disorder characterized by the presence of at least one manic episode. A manic episode is defined as a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood lasting at least one week that includes symptoms such as inflated self-esteem, impulsive behavior, increased rate of speech, and decreased need for sleep. As the term bipolar disorder suggests, afflicted individuals also experience the opposite of mania – depression. The result is an oscillation between extreme mood states that is often accompanied by severe distress and impairment and requires consistent and intensive medication management (the traditional remedy is a mood stabilizer such as Lithium, although many other classes of drugs have been shown to be effective for its treatment).

In the role of Pat Jr., Bradley Cooper (best known for his role in the raunchy Hangover films) shows heretofore-unseen range and talent. As is often the case with individuals with bipolar disorder, he plays Pat Jr. as remarkably charismatic and intense. Despite this, the portrayal of bipolar disorder is a mixed bag. Only in one terrific scene when Pat Jr. obsessively finishes a classic novel and storms into his parents’ bedroom in the middle of the night to deliver a rapid-fire rant about the book’s ending do we see a true manifestation of the disorder. Throughout most of the rest of the film, his tendency toward verbal and physical aggression and his obsessive thought patterns are the primary symptoms on display. Although these symptoms are not atypical of bipolar disorder, they are hardly the hallmarks and overlap with a wide range of other pathologies. There is nothing particularly dishonest or blatantly inaccurate about the depiction, but it pales in comparison to others that have been captured on film and television. For example, the award winning work of Claire Danes as a CIA agent with bipolar disorder on the cable drama Homeland could be studied alongside real life case vignettes by medical residents and psychologists (and should be studied by acting classes as well).

Much more successful is the depiction of borderline personality disorder in the character of Tiffany, the sister of Pat Jr.’s best friend’s wife. Interestingly enough, although hers is the most accurate and interesting portrayal of mental illness in the film, the label of “borderline personality disorder” is never applied to her. Rather she is referred to as “crazy,” “unstable,” “a sex addict,” and a variety of other terms that do not come close to representing the whole picture. Throughout the film we learn that Tiffany has a history of extreme emotional reactions, unstable interpersonal relationships, compulsive and impulsive sexual activity, difficulty controlling anger, and self-harm. These are the hallmarks of borderline personality disorder, a severe and impairing disorder, which has only begun to gain major attention in the past two decades (mostly due to the work of psychologist Marsha Linehan, who developed the most effective treatment known for the disorder – dialectical behavior therapy). As is the case with Pat Jr., we learn that she had traits and symptoms consistent with the disorder prior to a traumatic event that triggered full-blown pathology. In Tiffany’s case, it was the unexpected death of her husband.

Tiffany is bravely and beautifully played by Jennifer Lawrence, who is best known to audiences as Katniss Everdeen in the film adaptation of the wildly popular Hunger Games book series, but first came to attention in her Oscar-nominated role in the haunting drama Winter’s Bone in 2010. She has exquisite line delivery and is the rare actress who is as comfortable in wild comic moments as she is in explosive dramatic ones and as effective at displaying subtle heartbreak as she is at virulent rage. Her character’s pathology is best seen in a scene when she and Pat Jr. have a date at a diner. She is clearly smitten with him and tries awkwardly and ineffectively to steer his attention off of his cheating wife and on to her. One cutting comment of his deeply upsets her and her explosion is a stunning one, leading to her verbally eviscerating him on a public street. Rarely has the phenomena of “splitting” been so well depicted in cinema. “Splitting” involves an inability to integrate multiple aspects of another individual, resulting in a designation of someone as either “very good” or “very bad.” This is very common in borderline personality disorder and often results in individuals with the disorder rapidly and frequently oscillating between idealizing/loving and devaluing/hating important figures in their lives. This is what makes individuals with this diagnosis so hard to treat clinically and often so hard to be in relationships with.

The relationship between Pat Jr. and Tiffany is an extremely odd one. It involves enormous deceit, a fair amount of stalking, and offensive, blunt, and callous barbs repeatedly flung back and forth. Despite this, the incredible chemistry of Cooper and Lawrence (and some sharp writing) makes the audience root for them to fall in love. But is that really a good idea? A great deal of work in evolutionary and social psychology has focused on the factors that go into our selection of potential mates. We know that individuals across cultures and throughout history are attracted to others who share our attitudes, values, and various other characteristics. (If we want to speak in clichés, the research concludes that in general “birds of a feather flock together,” not that “opposites attract.”) We also know that individuals with mental illness are more likely to have unstable and unsuccessful romantic relationships and that this is enhanced when both individuals have mental illness. This seems especially the case for Pat Jr. and Tiffany, who each have limited social skills, primitive emotional processing, very underdeveloped emotion regulation skills, and a history of traumatic relationships. The film sweeps us up in their wildly unconventional romance, but I could not help but project a rocky, painful future for these two characters.

As if the story did not already have enough characters with mental illness, a third is thrown in. Pat Jr.’s father (obviously named Pat Sr.), is out of work and is deeply involved in sports betting. Pat Sr. clearly suffers from obsessive-compulsive disorder, an extremely impairing and prevalent anxiety disorder in which intrusive thoughts that produce uneasiness, apprehension, or fear are accompanied by repetitive behaviors aimed at reducing these unpleasant feelings. As is characteristic of the disorder, Pat Sr. engages in rigid and irrational thinking marked by superstition and unrealistic evaluations of event occurrence (which is clearly not an ideal set of traits for a gambler). He has difficulty relating to his son and feels an enormous amount of guilt for how Pat Jr. turned out. The subtlety with which Pat Sr.’s pathology is revealed is nicely realistic and quite effective. Although the relationship between the two Pats is not the primary focus of the film, it is arguably its most moving. This is mostly due to the stellar portrayal of Pat Sr. by film legend Robert DeNiro (who finally returns to high quality work after languishing in second-rate thrillers for the past decade).

Although Pat Jr., Tiffany, and Pat Sr. are nuanced and interesting characters, the film really fumbles with three others. As Danny, a friend of Pat Jr.’s from them mental institution, Chris Tucker is mostly a one note caricature of a mental patient, the type of cheap characterization that is completely out of sync with the others in the film. As Pat Jr.’s psychiatrist Dr. Patel, Anupam Kehr dispenses unhelpful advice (e.g., repeatedly telling the client to “figure out a way” to “get over it” rather than demonstrating skills, helping him generate potential solutions, and empathically validating his pain). Furthermore, in the most atrocious depiction of ethical violations in film since Anna Kendrick and Joseph Gordon-Levitt went on a date at the end of 50/50, Dr. Patel ends up shirtless and intoxicated in the family’s living room after a rowdy football game. The less said about this ridiculous, unfunny, and unnecessary plot development the better. And finally, despite her enormous talent (which was on display in her recent Oscar-nominated turn in the recent Australian crime drama Animal Kingdom), Jacki Weaver is unable to overcome the poorly written and woefully underdeveloped character of Delores, the family matriarch. It is true that in a family with such strong personalities and volatility, a wife and mother is likely to fall into a more passive role. However, while the characters’ indifference to her is painfully honest, the filmmakers’ lack of interest in her is an enormous missed opportunity. She clearly plays a huge role in how this dysfunctional family’s dynamics and the film would have been all the richer for exploring that facet.

The mix of stellar and poor characterizations result in a film that is never as good as it could be. I enjoyed it immensely, but it is certainly not without flaws. The acting is uniformly excellent and the story is an engaging one, but it fizzles out in the final act, sacrificing its edginess and honesty for an all-too-easy and contrived Hollywood ending. On the other hand, it is refreshing to see a risk-taking entry in the normally trite and cliché-ridden romantic comedy genre. Additionally, its lightness and laughs adds variety to the sea of Oscar contenders, which are excellent but tackle relentlessly depressing subject matter such as slavery (Lincoln and Django Unchained), violent global conflicts (Zero Dark Thirty and Argo), terminal illness (Amour), natural disaster (Beasts of the Southern Wild and The Impossible), and an excruciating mix of oppression, poverty, starvation, prostitution, exploitation, and war (Les Miserables). Indeed, I laughed heartily at the film and smiled wide when the credits rolled. Later reflection, however, highlighted the deep sadness that runs through these characters (and the film itself) and made me think about just how rocky the road ahead for these characters is likely to be.