I’m not sure about you, but when I hear Celine Dion belting out the last chorus of “My Heart Will Go On”, I seem to disconnect from reality and become totally immersed in a wave of emotion (one might even say that it’s a wave strong enough to sink a cruise ship). Although Celine may not do it for everyone, many people have an emotional connection with music. We also tend to associate so many emotionally powerful events in our lives with music. For example, many newlyweds will choose an emotional love song for their first dance at the wedding reception (which may or may not have been “their song” from when they were dating). At a high school commencement, the graduates often process out to a song that becomes their “graduation song” (mine was “Send Me on My Way” by Rusted Root). But even outside the context of these events, music plays an important part in people’s lives around the globe, across many different languages, cultures, and countries. Why is it, then, that we are so emotionally responsive to music? For me, it may be hearing that French-Canadian diva belting out the last note of “The Power of Love”, and for you it might be a different musical moment, but research indicates that there may be a physiological, or even neurological, connection between hearing emotionally powerful music and feeling moved.

One study published in Psychology of Music from 2004 by Nikki Rickard recently caught my attention. The researcher examined whether or not listening to emotionally powerful music would elicit greater physiological arousal (indicative of emotional intensity) compared to relaxing music, arousing (but not emotional) music, and an emotional film scene (with no music). The results showed that listening to emotionally powerful music produced the greatest increases in skin conductance and number of chills. In other words, listening to emotional music versus all the other previously mentioned situations caused people to sweat more and have more chills. Although their reliability and validity are not universally agreed upon, these measures have been used in the emotion literature as physiological indicators of emotional intensity. This seems to indicate that there is something about emotionally powerful music in its ability that can stimulate our emotions, but how is this actually happening? I might feel a chill or two when Celine sings a dramatic key change, but I don’t necessarily notice that my palms get all sweaty or anything. What, then, is the underlying mechanism responsible for music causing intense emotions?

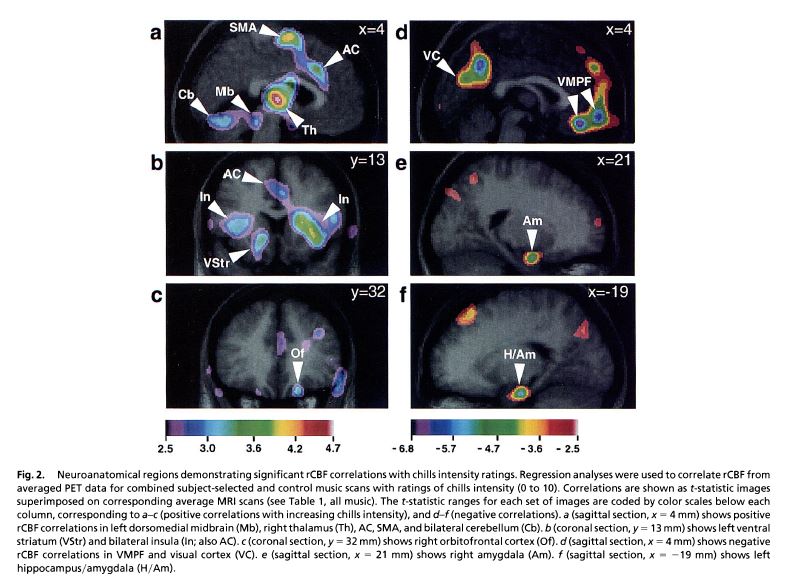

Interestingly, I found another study by Anne Blood and Robert Zatorre (2001) that offered me a glimpse of the answer I was looking for. They, too, had their participants listen to emotionally powerful music, but each person was in a PET scanner so that the researchers could measure brain activity. While listening to the music, participants reported feeling chills, similar to those discussed earlier. These chills were accompanied by increased heart rate and respiration patterns – but I was more intrigued by the pattern of activity within the brain! As the intensity of the chills increased (and arguably the intensity of emotion being elicited from the music), there was increased blood flow in brain regions that are involved in central reward and emotional pleasure. These areas of the brain are the same areas that govern the release the neurotransmitter known as dopamine, which is thought to be the underlying neurological response to rewarding stimuli (such as good food or good sex).

Wow! In other words, listening to Celine Dion in my car on my way home could be tapping into the same neural reward systems that I experience when I eat a delicious cheeseburger? These neural reward systems arguably exist, in part, to reinforce survival behavior. But perhaps they also exist not only to help us survive, but also to thrive. Although music may not be necessary for survival (a point that I’m sure many would argue against!), it may serve a purpose by enhancing our mental and physical well-being. More research is currently underway, investigating these relationships.

So, I encourage everyone to find their own “Celine Dion”—an artist, band, DJ, or some musical groove that you emotionally connect with. Take the time to submerge yourself in the sound, and let yourself experience those chills and sweaty palms – your brain may reward you for it.

Sources:

1. Rickard, N. S. (2004). Intense emotional responses to music: A test of the physiological arousal hypothesis. Psychology of Music, 32(4), 371-388.

2. Blood, A. J., & Zatorre, R. J. (2001). Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(20), 11818-11823.