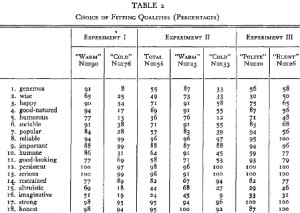

Solomon Asch may be best known in social psychology for his 1951 Conformity Studies in which he brought participants into a room with seven confederates—actors pretending to be other participants—and had them recount the length of a line. Before demonstrating that normative pressure can lead people to lie, Asch was one of the foremost researchers on impression formation. He was interested in how we judge others and their personality based off small bits of information. In 1946, he published his findings from several experiments in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology (which I highly recommend you read here). In the first experiment he describes, participants in one of two conditions heard read a list of character-qualities that were identical except for one word. The participants in the first group were told that the person was “intelligent, skillful, industrious, warm, determined, practical, [and] cautious” while the second group of participants were told the person was “intelligent, skillful, industrious, cold, determined, practical, [and] cautious.” The participants were then instructed to write a brief personality sketch of the person based on these character traits alone. Asch was curious how much, if at all, changing one word of the description would change the overall impression of the hypothetical person. Asch reports his findings from the first study alongside experiment two and three’s results in Table Two.

Experiment two and three were variations of experiment one, demonstrating that individuals naturally sort people into the “warm” or “cold” category in the absence of a specific descriptor and that “polite” and “blunt” could be substituted for warm and cold respectively. Because Asch ran his experiments almost 70 years ago, he reported his results as the percentages of people who endorsed a given trait in their sketch. Asch concluded that individuals form dynamic impressions of others, based on more valenced or important character traits first with supporting or peripheral traits given lesser weight. He makes his conclusions from the qualitative data he has, limited by the methodology of his time.

Reading his 1946 paper for the first time, I could not help but wonder whether Asch’s conclusions about personality inference would hold under modern statistical tests. Although most early social psychologists did not rely on p-values to determine a finding’s significance, the rigor from current-day testing may help further validate Asch’s research. I decided to embark on a (very nerdy) adventure exploring Asch’s data. To examine Asch’s findings with modern statistical rigor, I converted the reported percentages of subjects who had endorsed a characteristic back to the raw number of participants, based on the total N given at the top of each column in Table 2. I then proceeded to subtract the number of subjects who had endorsed a characteristic from the total N, to arrive at the number of subjects who did not endorse a trait for each condition. For example, in Experiment 1, I converted 91% of participants in the “Warm” condition who endorsed “generous” back to a total of 82 people. Subtracting 82 from 90, I found 8 individuals did not endorse “generous” in the “Warm” condition. Repeating the procedure for subjects in the Experiment 1 “Cold” condition, I found 6 people endorsed “generous” while 70 participants did not. After I had the total n for each cell, I ran a Chi-Squared test to determine if a significant difference in endorsement for generosity existed based on condition. I repeated this measure for each dependent variable and condition in all three experiments. For the super nerds out there like me, I have included my tables of results below.

The Chi-Square Tests for Independence generally support Asch’s qualitative claims, upholding his conclusion that character traits affect impression formation differentially. Although also finding the statistical significance of results he correctly predicted interesting, I want to focus on the few existing differences between Asch’s conclusions and the significance suggested by statistics. Determining “[c]ertain qualities are preponderantly assigned to the ‘warm’ person, while the opposing qualities are equally prominent in the ‘cold’ person,” (p. 264), Asch places “restrained” and “important” in the category of traits unaffected by his manipulation. Differences in “restrained” ratings reach statistical significance, however, for both Experiments I (χ2(1, N=166) =7.211, p=.007) and II (χ2(1, N=56) =7.623, p=.008) despite the seemingly similar numbers of individuals endorsing the trait. Their significance is driven by differential rates of endorsement, with individuals in the “cold” condition identifying the stimulus as “restrained” much less often than “warm” group subjects. Asch’s qualitative methods led him to commit a Type II error, failing to recognize a difference between conditions when one existed. The “restrained” data further support Asch’s conclusions, as Experiment III failed to replicate prior findings (χ2(1, N=46) =0.63, ns). Changing the manipulation trait from “warm”/”cold” to the “relatively peripheral” characteristics (p. 266) of “polite”/”blunt” altered the impression formation, as Asch predicted. Looking at differences in “importance” in Experiment I, a significant difference existed between conditions. “Cold” primed participants endorsed the stimulus individual as “important” more often than “warm” primed participants (χ2(1, N=166) =7.308, p=.007). The differential rate of endorsement failed to hold statistically, however, as the χ2 values for Experiment II and III did not reach significance for differences in “importance” ratings (χ2(1, N=56) =0.011, ns and χ2(1, N=46) =0.36, ns), respectively). The discrepancy leads one to wonder what about assigning participants to a category versus allowing them to describe the perceived individuals as “warm” or “cold” leads them to change their evaluation of a perceived person.

Generally, Asch’s qualitatively-based conclusions hold true, with discrepancies only further validating his claims. Erring on the conservative side, he underestimated the effect of central personality characteristics to affect perceptions of “restraint” and “importance.” In all other cases, his assertion that warmth and cold differentially change impression formation more strongly than politeness resonate with greater validity, reaffirmed by modern statistics.

My Table 2. Chi-Square values for all dependent variables, Experiments I-III

Dependent Variable Traits

Experiment I

Experiment II

Experiment III

Generous

χ2(1, N=166) =114.552, p=.000

χ2(1, N=56) =15.77, p=.000

χ2(1, N=46) =.033, ns

Wise

χ2(1, N=166) =27.207, p=.000

χ2(1, N=56) =8.928, p=.003

χ2(1, N=46) =1.865, ns

Happy

χ2(1, N=166) =55.98, p=.000

χ2(1, N=56) =7.555, p=.006

χ2(1, N=46) =.494, ns

Good Natured

χ2(1, N=166) =101.913 p=.000

χ2(1, N=56) =8.662, p=.003

χ2(1, N=46) =3.982, p=.046

Humorous

χ2(1, N=166) =66.632, p=.000

χ2(1, N=56) =22.08, p=.000

χ2(1, N=46) =2.616, ns

Sociable

χ2(1, N=166) =52.151, p=.000

χ2(1, N=56) =8.662, p=.003

χ2(1, N=46) =1.545, ns

Popular

χ2(1, N=166) =54.757, p=.000

χ2(1, N=56) =10.336, p=.001

χ2(1, N=46) =8.16, p=.004

Reliable

χ2(1, N=166) =2.126, ns

χ2(1, N=56) =.068, ns

χ2(1, N=46) =1.329, ns

Important

χ2(1, N=166) =7.308, p=.007

χ2(1, N=56) =.011, ns

χ2(1, N=46) =.036, ns

Humane

χ2(1, N=166) =50.39, p=.000

χ2(1, N=56) =12.41, p=.000

χ2(1, N=46) =1.529, ns

Good Looking

χ2(1, N=166) =1.418, ns

χ2(1, N=56) =1.825, ns

χ2(1, N=46) =2.018, ns

Persistent

χ2(1, N=166) =1.191, ns

χ2(1, N=56) =1.461, ns

ns, 100% subjects endorsed it

Serious

ns, 100% of subjects endorsed it

χ2(1, N=56) =2.976, ns

ns, 100% subjects endorsed it

Restrained

χ2(1, N=166) =7.211, p=.007

χ2(1, N=56) =7.623, p=.006

χ2(1, N=46) =.063, ns

Altruistic

χ2(1, N=166) =42.28, p=.000

χ2(1, N=56) =9.81, p=.002

χ2(1, N=46) =1.238, ns

Imaginative

χ2(1, N=166) =19.078, p=.000

χ2(1, N=56) =8.991, p=.003

χ2(1, N=46) =.003, ns

Strong

χ2(1, N=166) =1.094, ns

χ2(1, N=56) =.068, ns

ns, 100% subjects endorsed it

Honest

χ2(1, N=166) =1.936, ns

χ2(1, N=56) =2.209, ns

χ2(1, N=46) =4.172, p=.041