Some of us are more prone to worry than others. Although we often throw the word “anxiety” around, it can be helpful to distinguish worry, sometimes called “anxious apprehension,” from the kind of anxiety you feel in your body, also known as “somatic anxiety” or “anxious arousal.” As opposed to somatic anxiety, which you might think of as those pesky physical responses you get to anxiety such as muscle tension and increased heart rate, worry is largely a verbal process associated with thoughts like, “what if the worst happens” (1). Neuroscience research even suggests that worrying activates the same parts of your brain that are most active when you speak aloud (2–4).

Cognitive psychologists have long discussed both the potential adaptive functions and pitfalls of worrying. In terms of benefits, spending time worrying about potential future dangers and threats could promote preparation for adverse events. For example, worrying about the outcome of an exam can prompt us to spend time studying for that exam. Worry regarding COVID-19 may boost the likelihood that we wear a mask. Because there can be benefits to worry, psychologists often differentiate normative vs. excessive worry.

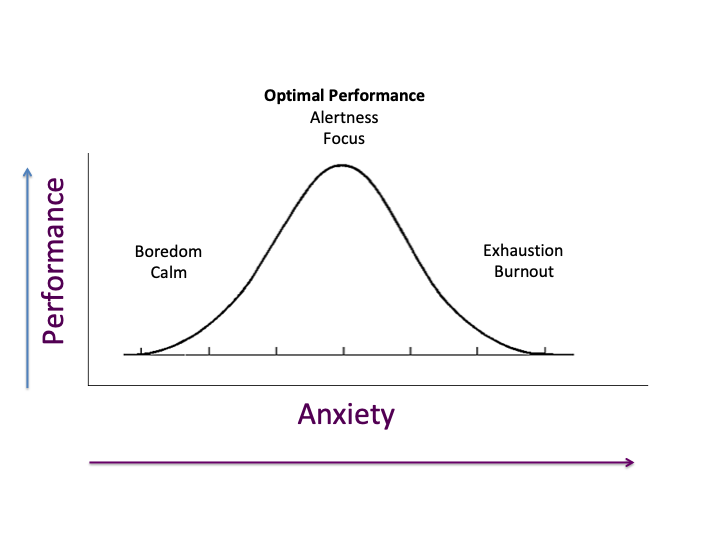

Bell-shaped curve demonstrating relationship between anxiety and performance as proposed by Yerkes and Dodson (1908). Graphic by A. Guha.

The extent to which we feel anxious is hypothesized to relate to performance in a bell-curve shape, with the exact shape of the bell differing depending on task. Per the Yerkes-Dodson law proposed by Robert Yerkes and John Dodson, too little anxiety results in inadequate attention and interest, whereas too much anxiety impairs performance (5). These researchers suggest that between these extremes, a point of optimal pressure to perform may promote success.

Excessive or uncontrollable worry is not only associated with generally worse performance, it also causes distress and makes us less effective. As we become more worried, instead of that worry helping us prepare for potential negative outcomes, it can become crippling and make us want to withdraw and avoid (6). Below are some steps you can take to manage your worry:

Learn when your worry is productive vs. unproductive

The first step to managing your worry more effectively is to take a moment to identify if your worry is productive or unproductive. If your worry thoughts correspond to specific steps you can take, use that worry to help you problem solve. Make a list or devise a game plan for the target of your worry. Are you worried about all the work you have to do on Monday? Take a few minutes to write down your to-do list and schedule out when on Monday you’ll address each item. This is a way to channel that worry into productivity that will not only help you to feel prepared but also should help to reduce your anxiety.

How can you tell if your worry is unproductive? A big indicator is if your worries seem nebulous or non-specific. Worry is also unproductive if you have already done everything you can to prepare for the thing making you anxious, yet still notice yourself having trouble controlling your worry. If you look back at the Yerkes and Dodson bell curve above, this is the type of worry on the right side of the curve. Unproductive worry is often the source of “anxiety spirals,” or cycles of uncontrollable worry, because it seems to persist even after anxiety has pushed us toward effective preparation. If you notice yourself caught up in a worry spiral, then you are most likely dealing with unproductive worry. The strategies outlined below are specifically helpful for tackling this unhelpful worry–

Challenge your worries

In Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), a primary focus of treatment is identifying, challenging, and reframing unhelpful thoughts, including worries (7-8). The first step is identifying a thought. Say out loud or write down what your worry thought is. Now that you hear or see that worry, does it seem irrational? If a friend told you this worry, would you consider it unrealistic or unlikely? Take a moment to acknowledge that your worry may not be logical. Use evidence from your past experience to help you challenge how realistic your worry thought is. In similar situations in the past, how did things turn out? Did the terrible outcome you are fearing occur? How likely is it really that this worried outcome will occur? Will it be as catastrophic as it feels right now if the worried outcome were to occur? Is a different, less anxiety-provoking outcome more likely than the one you fear now?

Our worries are often so automatic we do not really think through how realistic they are. When we really think about them, they are often unlikely or irrational. After you have identified and challenged a thought, it can then be helpful to rephrase it. This process is termed cognitive restructuring in CBT. Instead of the thought, “I might fail my test next week, and that would mean I am a failure,” you could restructure this thought to something like, “I’ve studied really hard for this test so it is unlikely I will fail. Even if I do poorly on my test, it does not mean I am a failure.” Restructuring definitely takes practice, so it can be helpful to use an app to help, like the CBT Thought Diary App: https://apps.apple.com/us/app/cbt-thought-diary/id1010391170.

Put distance between yourself and your worries

This approach is a primary focus of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; 9) philosophy. This school of thought suggests that it is not worry in itself that causes us distress, but the sense that we are glued to our worry thoughts. Feeling glued to our worry, feeling like it is part of us, can increase the sense that our anxiety is overwhelming and uncontrollable. When we get tangled up in our worries and feel attached to them, we give them power over us. The process of detaching ourselves from our worries is termed cognitive defusion (10). In contrast to the concept of challenging your worries as described above, cognitive defusion includes acknowledging and accepting that you are having worry thoughts, giving yourself distance from them, and reminding yourself that you are *not* your worries.

ACT emphasizes the importance of the language we use to describe our thoughts and feelings. Are you saying, “I am worried” or “I am anxious”? Instead, try to see yourself as an observer of your thoughts and feelings. Instead of “I am worried” or “I am anxious,” try saying to yourself, “I am having the thought that ___” or “I feel ____.” Becoming a witness to our own thoughts and feelings helps us to get distance from them. It can also be helpful to find ways to describe your thoughts and feelings very matter of factly and without judgment. For example, saying, “oh, there is worry” when a worry pops up. Instead of prescribing an evaluative label on the thought or feeling as being good or bad, simply name the thought or feeling. Acknowledging and labeling our worries without giving them judgment labels reduces their power over us.

In addition to altering the language we use to describe our worry, visualization exercises can be very helpful for cognitive defusion. A popular practice is called “leaves on a stream.” During this practice, you imagine yourself sitting beside a stream. As you notice thoughts arising, you simply imagine placing those thoughts on leaves, setting them on the stream, and watching them float by you. You can also imagine placing your thoughts on clouds and watch them slowly drift away. These types of visualizations can help you feel more engaged with the process of cognitive defusion and provide structure to the practice.

Approach the things you want to avoid

As mentioned above, worry makes us withdraw and avoid. Have you ever noticed that when you are anxious about writing a paper, it becomes easier and easier to keep putting it off? Have you also noticed that as you continue to put off writing the paper, you start to feel more anxious? Worry makes us want to avoid whatever feared future event we are concerned about. On the one hand, this may seem advantageous because it means we can continue not to tackle the feared event. The downside is that our anxiety continues to build as we avoid. Worry sometimes feels like it protects us from feared outcomes, yet actually serves to maintain our worry and apprehension.

CBT and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) suggest taking worry as a sign to avoid avoiding (11). By confronting the feared event or situation we are worried about, we end up breaking the worry cycle. 99% of the time confronting the feared event or situation also demonstrates to us that our worry is out of proportion. The worry we have about presenting to our peers often largely outweighs how scary it ends up actually being to present, or how bad it actually is when we fumble or make a mistake during that presentation. If you notice consistent worries around a specific outcome, task, event, or situation, take that as a sign that you need to approach that situation instead of avoiding it. This will help to reduce worry at the source.

Find ways to practice accepting uncertainty

Many psychologists have suggested that an inability to tolerate uncertainty drives and sustains excessive worry (12). Take a moment to remember that we cannot predict the future. If you’ve taken the steps to channel productive worry into problem solving and effective action, then you have done all you can. At this point, all we can do is acknowledge and accept that we cannot control the future. Unfortunately, practicing this type of acceptance is not a “one-and-done” deal. We have to keep practicing acceptance over and over again. When you notice that worry cycle starting up, remind yourself that the future is uncertain and adopt a flexible mindset. Try to roll with things even when you cannot control them.

Orient yourself to the now

Worry usually focuses on the future. Our anxious thoughts generally pertain to fears of what is yet to come. Instead of focusing on the future, root yourself in the present moment. This is a core principle of mindfulness. Remind yourself that the feared future event or outcome is not happening in this moment. Redirect your focus to the present. You can even say to yourself, “back to now,” or “back to this moment.” Mindfulness techniques can be especially helpful for this. When your mind wanders to the future, gently bring it back to something that grounds you in the present moment like the way your body feels in your chair, the way your chest rises and falls with each breath, or the way your feet help you feel rooted and grounded as they rest on the floor.

Summary

Psychology research has demonstrated that there are a number of ways we can work through our anxiety. If you find yourself identifying with the label “worrywart,” try implementing some of these techniques. You may find that one approach works best for you while others are less effective. You might also find that you prefer certain approaches depending on the situation.

References

-

Hirsch CR, Mathews A. A cognitive model of pathological worry. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(10):636-646. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2012.06.007

-

Guha A, Spielberg JM, Lake J, et al. Effective Connectivity Between Broca ’ s Area and Amygdala as a Mechanism of Top-Down Control in Worry. Clin Psychol Sci. 2019. doi:10.1177/2167702619867098

-

Engels AS, Heller W, Mohanty A, et al. Specificity of regional brain activity in anxiety types during emotion processing. Psychophysiology. 2007;44(3):352-363. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00518.x

-

Warren SL, Crocker LD, Spielberg JM, et al. Cortical organization of inhibition-related functions and modulation by psychopathology. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7(June):271. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00271

-

Teigen KH. Yerkes-Dodson: A Law for all Seasons. Theory Psychol. 1994. doi:10.1177/0959354394044004

-

Borkovec TD. The nature, functions, and origins of worry. In: Worrying: Perspectives on Theory, Assessment, and Treatment. ; 1994.

-

Clark DA. Cognitive Restructuring. In: The Wiley Handbook of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. ; 2013. doi:10.1002/9781118528563.wbcbt02

-

Beck AT. Cognitive therapy: Nature and relation to behavior therapy. Behav Ther. 1970. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(70)80030-2

-

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change.; 2012.

-

Assaz DA, Roche B, Kanter JW, Oshiro CKB. Cognitive Defusion in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: What Are the Basic Processes of Change? Psychol Rec. 2018. doi:10.1007/s40732-017-0254-z

-

Linehan MM. DBT skills training handouts and worksheets. DBT Ski Train handouts Work. 2015. doi:alcalc/agv004

-

Dugas MJ. Intolerance of uncertainty and problem orientation in worry. Cognit Ther Res. 1997. doi:10.1023/A:1021890322153