*This article was authored by Zhouzhou (Jo) He and Razia Sahi as part of the 2021 undergraduate series.

The human mind is a complex place, and psychological phenomena seem obvious until we have to explain when, why, and how they happen. Researchers can make it look easy, but the process of forming a testable hypothesis, designing a study to test this hypothesis, and carefully following up on your results to rule out alternative explanations is no simple feat. Indeed, multiple rounds of the research cycle are often needed before we can reasonably support a given conclusion. Before falling into a rabbit hole, let’s focus on breaking down one cycle of the research process.

How do we get answers to our questions about human behavior and the human mind? How do we design and interpret studies rigorously? In this article, we will walk you through the steps that go into planning and testing a hypothesis with a series of studies using recently published work from the UCLA Social Affective Neuroscience and Development (SAND) Lab as an example. We’ll especially focus on how to rule out alternative interpretations when testing a hypothesis.

1. What question do you have about human psychology?

Questions kickstart and guide the research process. Maybe you’re interested in decision-making, or memory, or the causes of depression. Even in well-established fields, there are endless questions about human psychology just waiting to be asked! Be sure to write out explicitly the question you have in mind so that you have a clear understanding of what you’re interested in, and look carefully at the literature to see what has already been explored.

In recent work from SAND Lab, Sahi and colleagues (Sahi, Ninova & Silvers, 2020) wondered: is it more effective to have others regulate our emotions for us than it is to regulate on our own? Answering this question offers a new way to think about how well-being can be improved, and probes the ways that social support can explicitly shape emotional experiences.

2. What is a more specific way of framing your question?

Oftentimes, your initial question will be broad. In order to obtain as accurate of an answer as possible to your question, it is necessary to break down the question into smaller components by identifying key terms in your broad question. You can ask yourself: how can you measure the concepts you are interested in? Which of these measures most closely map onto the everyday phenomenon you are interested in? What are some natural limitations of studying this phenomenon in the lab?

Returning to our example study, the research team realized there were many ways to break the question down: What does emotion regulation mean? What does it look like when others regulate our emotions, and how do people regulate emotions on their own? What is considered effective emotion regulation?

Reviewing existing research can be helpful at this point. From the literature review, the study team saw a great deal of research on a specific emotion regulation strategy: cognitive reappraisal. Reappraisal is an emotion regulation strategy that involves changing how we feel by changing how we think about the emotional situation (Gross, 1998b). The study team thought, anecdotally, that people often get help with changing how they think about an emotional situation. For example, imagine getting a call saying you did not get your dream job. Many people may turn to a close friend or relative to share the distressing news. In turn, the support giver may say something like “don’t worry – there are a lot of great opportunities out there and you’re going to find a job that’s the right fit for you.” In such a case, it might be easier to believe your trusted friend’s positive interpretation of the situation that trying to change your interpretation of the situation on you own.

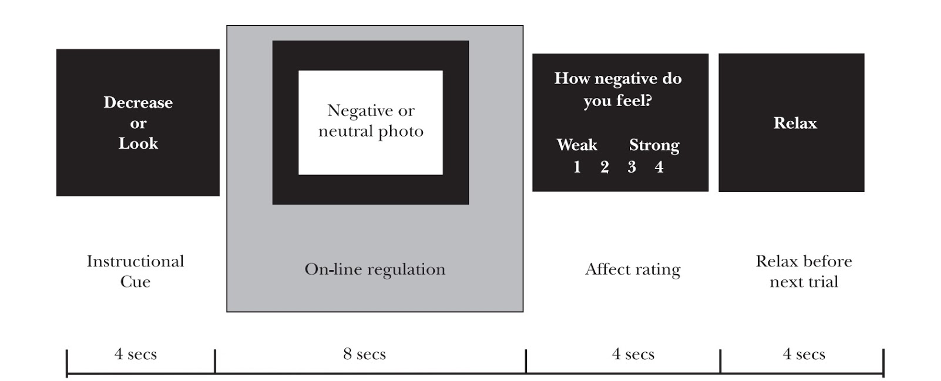

So, there is a good amount of research on how people use reappraisal to regulate their own emotions (Buhle et al., 2014), meaning there are a plethora of laboratory tasks that the study team can consider using to assess effective emotion regulation in a “solo” context. For example, a common laboratory task (Ochsner et al., 2004) used to study solo reappraisal instructs participants to think differently upon seeing a negative image in order to decrease how negatively they feel (see fig 1). For example, upon seeing an image of someone injured in an accident, one might feel a sense of pity and distress. When instructed to decrease how negatively they feel, participants might reappraise this situation by thinking about how the situation could improve or how things are not as bad as they seem (e.g. the person may fully recover).

Fig 1 A standard laboratory task to study solo reappraisal (McRae et al., 2008)

These self-regulatory tasks provided a basis for Sahi and colleagues to develop a novel emotion regulation task for studying social emotion regulation. To modify the task for a social context, instead of prompting participants to think in a way that makes them feel less negatively about the images, researchers played audio clips of friends reinterpreting the stimuli during reappraisal trials. Using the earlier example of an accident, instead of instructing the participants to reinterpret the image themselves, participants would listen to their friend say “The person can fully recover” during the social emotion regulation (social ER) trials. These listening trials would be interspersed with passive viewing trials (i.e. look at the image as they normally would) of negative and neutral images. With the social and self regulatory tasks prepared, the study team could experimentally compare whether having others reinterpret an emotional situation for an individual is more effective than having the individual reinterpret for themselves.

3. What else do we need to think about in creating the experiment?

With a specific research question and paradigm in mind, and an idea for how to test it, here are some additional things researchers will have to break down:

a. What are the variables in question? Variables are things that can be controlled, changed or measured in an experiment. In our example, the independent variable (the feature manipulated) is the type of reappraisal (social vs solo) and the dependent variable (the outcome measured) is self-reported negative affect.

b. How can you control extraneous influences? In the example study, the study team attempted to reduce variability in the social ER condition by (i) inviting only female friend pairs to the study (because of potential gender differences in reappraisal (McRae et al., 2008) that could not be examined in the current sample); and (ii) standardizing the reinterpretations across friend pairs (i.e. providing a reinterpretation script for the support-giver), Additionally, the study team made sure they used comparable negative images across the passive viewing, reinterpretation, and listening conditions, and counterbalanced image sets across participants

c. How can you measure your dependent variable? In the example study, the study team asked participants to rate how negative they felt on a 4-point scale (1 = not bad at all; 4 = very bad) at the end of each trial.

d. What are your specific hypotheses? What do you predict is the relationship between the variables of interest? Write them out! In the example study, Sahi and colleagues tested three competing hypotheses regarding the efficacy of social ER: (1) social ER is more effective than solo ER; (2) solo ER is more effective than social ER; or (3) social and solo ER are equally effective. People benefit from social ER and solo ER in daily lives, but which strategy is more effective? Answering this question may inform better emotion regulation strategies to improve physical and mental health.

4. What are your results?

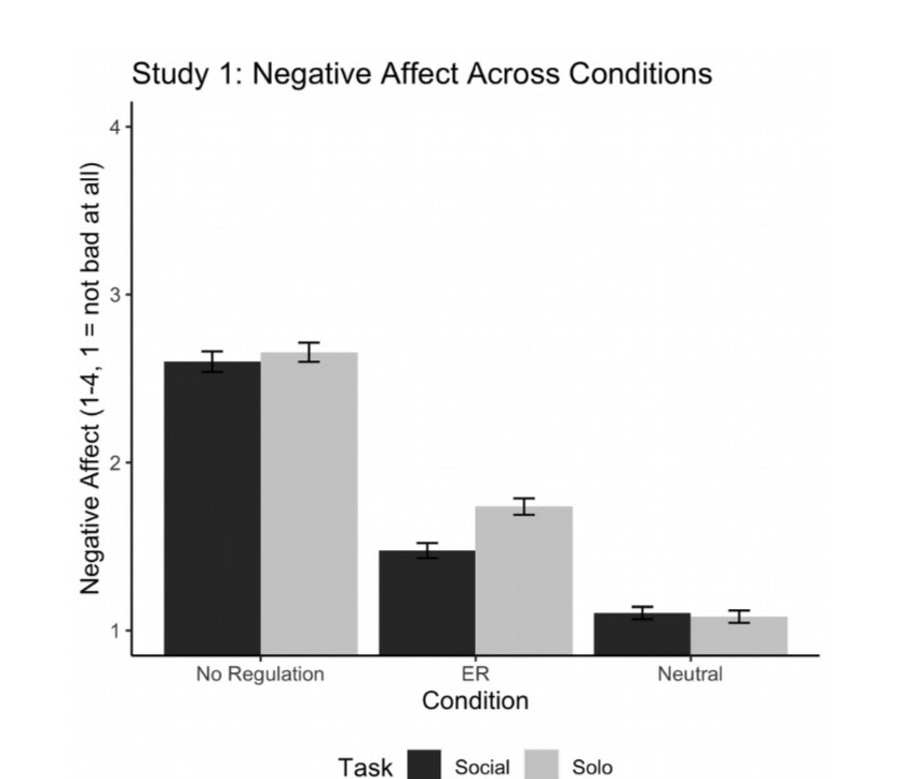

Fig 2. Does social help affect emotion regulation outcomes? (Sahi, Ninova, & Silvers, 2020)

What did you find? Compare across the conditions in your study. Describe the relationship between the variables in your study. Did what you find surprise you?

In the example study (fig 2), participants felt less negative affect when viewing neutral photos than when viewing negative photos (neutral vs. no regulation). Participants felt less negative affect when reappraising negative photos than when passively viewing negative photos (emotion regulation vs. no regulation). Finally, participants reported feeling less negative affect when listening to friends reappraise negative images (social ER) than when reappraising negative images on their own (solo ER). Fascinating! However…

5. What do your results mean???

At this point, generate some preliminary ideas about what your results mean. Are there other alternative interpretations of the study’s findings? What are some elements that are common or different across the conditions that could also explain the study results? In the example study, social ER may be more effective in down-regulating negative affect than solo reappraisal.

However, it is possible that the quality of reinterpretations in the social ER condition was better than that in solo reappraisal since the reinterpretations were scripted by the researchers for the social ER condition for the purpose of standardizing the reinterpretations across pairs. With this set-up, reinterpretations generated by the research team may be inherently better in quality than those participants generated themselves during the solo task, potentially explaining why the social task was more effective.

It is also possible that merely hearing a friend’s voice is enough to reduce negative affect irrespective of what they say. In the social ER conditions, hearing their friend’s voice, regardless of the reappraisal, could have been more comforting or distracting than doing this task alone.

6. Ruling out alternative explanations

It might be disheartening to find that there are multiple explanations for your results, and that even more studies have to be conducted to meaningfully interpret your findings. This is normal! Science is an iterative process; having to do more studies doesn’t mean your previous study was poorly designed or that you’re a bad researcher. In fact, good studies often focus on very specific features in a very specific context. Since human beings are so complex, we need multiple studies to replicate findings and test relationships in different contexts for a more holistic understanding of a phenomenon.

7. Repeat!

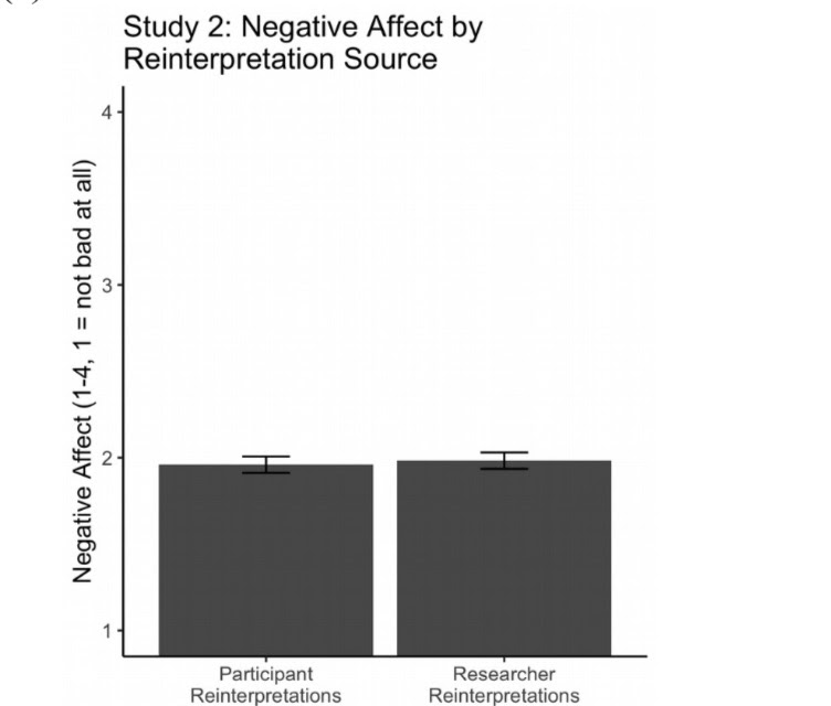

Fig 3. Does negative affect change depending on who generated the reinterpretation script? (Sahi, Ninova, & Silvers, 2020)

Practically speaking, then, how can alternative explanations be ruled out? One way to rule out the possible confounds you’ve isolated is to repeat steps 1- 7 again. For example, the study team wondered in step 5 whether the quality of reinterpretations were significantly different in the social task than the solo task. Sahi and colleagues directly tested this question in a second study by creating a new script using reinterpretations that participants came up with while trying to regulate on their own. They then had new participants complete a social ER task using a mix of these participant-generated reinterpretations and reinterpretations from the original script. Thus, the study team could assess whether the researcher-generated reinterpretations were better than those participants came up with on their own by seeing how the new batch of participants responded to these different reinterpretations. They found no difference in how effective these different sets of reinterpretations were in reducing negative affect, suggesting that the difference between the two tasks was not attributable to the quality of the reinterpretations (fig 3).

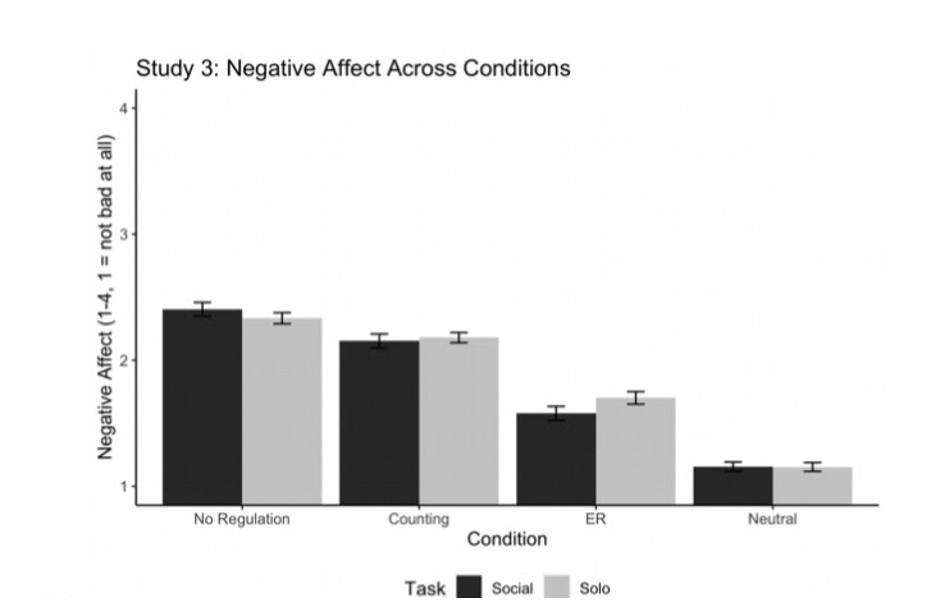

Fig 4. Does social help reduce negative affect across domains, or is the effect specific to the social emotion regulation task? (Sahi, Ninova, & Silvers, 2020)

To rule out the possibility that hearing a friend’s voice is enough to down-regulate negative affect regardless of what they may say, the study team created a third study that included a matched counting condition where participants counted by themselves or heard their friend counting. The study team chose to include this counting condition as their baseline condition because they could control the content of the condition across social and solo tasks and across participants, and because it was a task that could be presented to participants as being a potentially helpful meditative activity during negative affective situations. In other words, the study team examined whether social interaction (i.e. hearing a friend count calmly) reduced negative affect as compared to a matched solo condition (i.e. counting calmly alone). Was a “mere presence” effect triggered by hearing the friend’s voice enhancing the efficacy of social ER, irrespective of the ER strategy being implemented? If so, then hearing a friend’s voice should reduce negative affect even when the friend is not using reappraisal.

The study found that participants’ negative affect was not significantly different between the social counting condition and the no regulation condition. However, participants experienced lower negative affect in the social ER condition compared to the no regulation condition (fig 4).

8. Future Directions

Yay! We have now gleaned something interesting about human psychology. You might be feeling a bit wistful that the research process is over too fast, or maybe you’re curious about other topics in psychology. As mentioned earlier, the research process is never over. There is always space to generate new questions based on what your study results imply.

In the example study, researchers were curious about whether social emotion regulation is more effective than regulating alone, and whether the quality of reinterpretations or the mere presence of a friend possibly accounted for such a difference. While they ruled out these two alternatives, it remains an open question: what mechanism does explain why social regulation was more effective than regulating alone? Could it be because people are outsourcing cognitive effort required to self-regulate? Or could it be because social ER helps us adopt a more distanced view of the negative emotional experience? The study team can test the former by examining whether competing cognitive demands disrupt solo ER to a greater extent than social ER. The study team can also test the latter through post-hoc interviewing of participants. The research process never ends, when the goal is to understand the human mind!

What do your studies imply about human psychology, and what are some next steps you can take?

References

Buhle, J. T., Silvers, J. A., Wager, T. D., Lopez, R., Onyemekwu, C., Kober, H., … & Ochsner, K. N. (2014). Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: a meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cerebral cortex, 24(11), 2981-2990.

Gross, J. J. (1998b). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

McRae, K., Ochsner, K. N., Mauss, I. B., Gabrieli, J. J., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Gender differences in emotion regulation: An fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal. Group processes & intergroup relations, 11(2), 143-162.

Ochsner, K. N., Ray, R. D., Cooper, J. C., Robertson, E. R., Chopra, S., Gabrieli, J. D. E., & Gross, J. J. (2004). For better or for worse: Neural systems supporting the cognitive down- and up-regulation of negative emotion. NeuroImage, 23(2), 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.030

Sahi, R. S., Ninova, E., & Silvers, J. A. (2020). With a little help from my friends: Selective social potentiation of emotion regulation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

Thumbnail by Simone Secci on Unsplash.