This November, American voters will have to decide between re-electing Donald Trump or electing someone new. In this case, electing a new candidate does not equate with electing a young candidate. To date, Donald Trump (age, 73) is the oldest president to be sworn into office, but both of his Democratic competitors, former Vice President Joe Biden (age, 77), and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders (age, 78), would surpass him on that front (Ling, 2020). The age of each of the two Democratic front-runners has been called into question because people are wondering if their age will affect their ability to effectively lead the country (e.g., Bokat-Lindell, 2019). The average U.S. presidential age at the inauguration is about 55 years old, which is 20 years older than the age requirement set out by the Constitution; however, there is no upper age limit in place. This leads to an important question: How important is a candidate’s age when deciding who to vote for?

This seems like a reasonable question to ask considering that evidence demonstrates how aging is associated with declines in everyday cognitive abilities, such as working memory, processing speed, and executive functioning (McGillivray, Friedman, & Castel, 2012). When tested in the laboratory, higher levels of these cognitive abilities are linked to more success in everyday life. Older adults may not perform as well on traditional memory tasks due to cognitive declines in working memory and attention associated with aging; however, not all cognitive functions are affected to the same degree, nor are all types of memory (McGillivray et al., 2012). For example, a typical memory experiment often requires participants to study multiple lists of words and then participate in free recall tests (Castel, 2008). Episodic memory, or the ability to remember everyday experiences, typically declines due to aging, but prospective memory, or the ability to remember to do something in the future, may remain intact. In one study both older adults (recruited from retirement homes) and younger adults (recruited from a university) were asked to mail a stamped postcard on a specific date ranging from 1 to 28 days in the future (McBride, Coane, Drwal, & LaRose, 2013). The younger adult data followed a typical forgetting curve for retrospective memory tasks: prospective memory performance declined more rapidly at the shorter delays and more gradually at the longer delays. The older adults only showed a decrease in prospective memory performance at the 28-day delay. These results suggest that older adults may experience less of a decrease in prospective memory performance than younger adults.

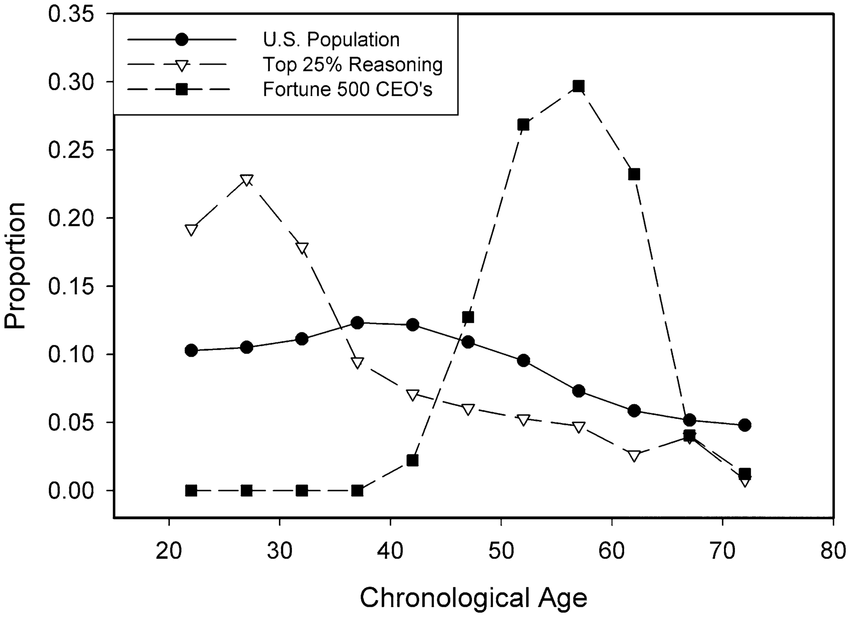

Further, it is important to consider that these abilities are measured with experimental tasks and paradigms. When considering whether or not age affects job performance, a more realistic experimental paradigm may tell us more about real-life functioning than a traditional lab task. Figure 1 shows three distributions: the proportion of the U.S. population ages 20-75, the top performers on the reasoning composite from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition (WAIS), and the chief executive officers (CEOs) of Fortune 500 companies as of December 2009 (Salthouse, 2010). According to this figure, older adults are not in the majority age demographic in the U.S. population, nor are they in the majority of top scorers on the WAIS. Yet, they are the dominant age group in the CEO category. The average ages of both CEOs of Fortune 500 companies and U.S. presidents range from 55-58 years of age, which suggests that many older adults hold these types of leadership roles. Figure 1 eloquently captures the discrepancy between cognitive declines in older adulthood and the considerable number of older adults filling leadership positions. You could make the argument that the driving force behind the connection between age and leadership is time: aging provides the opportunity for growth, experience, promotions, etc. This is a valid point to consider, but is it just that older adults have more opportunities to fill these positions or that more time is necessary to gain certain traits that are key to effective leadership?

Figure 1

Note. Reprinted from “Consequences of Age-Related Cognitive Declines”, by Salthouse, T., 2010, Annual Review of Psychology, 63, p. 201-226.

I turned to the book, Better with Age: The Psychology of Successful Aging, to answer this question. Older adults are often successful in the workplace despite performing lower on cognitive tasks when compared to their younger counterparts in part because of the wisdom factor. “Wisdom can be thought of as the ability to think and act using prior knowledge, past experiences, common sense, and insight (Castel, 2019b).” For example, young drivers may take more risks when driving and get into more car accidents when compared to older adults who tend to stick to familiar routes and refrain from driving when distracted or at night. Wisdom is a difficult attribute to test, although some researchers have conducted studies on wisdom that have produced interesting results. In one such experiment, older adults (senior citizens) and younger adults (college students) were asked to make decisions between different hypothetical discount cards (Tentori, Osherson, Hasher, & May, 2001). Each card offered a particular discount on a fictional purchase: either 15, 25, or 26 percent off of a minimum purchase price of either 20, 45, or 100 dollars respectively. Participants in one group were asked to decide between cards A or B, while participants in a second group had the option to choose between cards A, B, or C. Whether or not C is an option, B always gives a better discount. Younger adults were more likely to make an irregular decision than older adults, which means that they were less likely to choose B—the best option—when C was present than when C was absent. Younger adults’ choices were swayed simply by having more, new options available. Older adults may have used their experience in making financial decisions to guide them throughout this task. Decision-making is a large part of leadership, and this evidence suggests that experience may aid older adults in certain problem-solving tasks.

Wisdom can come in many forms and can guide problem-solving efforts in social situations as well as in tasks of logic (Castel, 2019b). In a study involving younger (ages, 25-40), middle-aged (ages, 41-59), and older (ages, 60-90) adults, participants were asked to read a series of stories centered around intergroup and interpersonal conflicts (Grossmann et al., 2010). After reading the stories, participants predicted how the conflicts would resolve if the story continued. Responses were analyzed using a code developed by a group of wisdom researchers and professional counselors. The task measured six dimensions that were derived from the most frequently cited characterizations of wisdom from the psychological literature, including using multiple perspectives, higher-order reasoning schemes, and compromise. The older adult group scored higher on these dimensions than the other two age groups, suggesting that older adults are more likely to use social reasoning than younger adults. This is a special kind of wisdom that improves with age likely due to more experience with interpersonal conflicts. The authors of this study even suggested that older adults should be involved in more roles involving legal decisions and intergroup negotiation! This evidence suggests that people may become more cooperative as they age. Cooperativeness is a key characteristic of effective leaders (Gachter, Nosenzo, Renner, & Sefton, 2010): from dealing with foreign governments to passing legislation to delegating tasks to Cabinet members, the ability to compromise and negotiate is essential to any presidential administration.

According to economists, another key characteristic of effective leaders is optimism (Gachter et al., 2010). Older adults tend to focus on positive information over negative information, which is a phenomenon often referred to as the positivity bias (Castel, 2019a). Despite evidence to support this theory, many people hold negative stereotypes about aging. Television often portrays “grumpy” older characters, and this may be due to a difference in affect amongst age groups. For example, younger adults smile and laugh more often on average than older adults, who tend to have a more stable affect. Historically, presidents have had to appear calm in the face of economic recessions, wars, etc. It is important for leaders to remain optimistic (within reason) in stressful situations so that those who look to them for guidance do not resort to panic. In addition, experience helps us to regulate our emotions as we age, which also may help older adult leaders provide stability for their people.

Whether or not you believe there should be an age limit on being the president, it is becoming clearer in the polls as the weeks go on that voters will likely be electing a septuagenarian as president this year. It is important to consider the benefits of having a leader who is an older adult as well as the possible downsides. Referring back to Figure 1, older adults fill many of our nation’s leadership positions despite declines in cognitive functioning (Salthouse, 2010). It is still somewhat unclear as to why these cognitive declines often do not translate to lower levels of functioning for older adults in the workplace, but it is most likely due to several factors. Wisdom gained through life experience certainly makes older adults viable candidates for leadership as do other qualities associated with older adulthood, such as cooperativeness and optimism. Personality, attitude, and motivation may also play large roles in the success of many older working adults (Salthouse, 2010). In the case of the 2020 election, voters will have to use their own decision-making skills to choose the best older adult for the job!

References

Bokat-Lindell, S. (2019, September 19). Are Biden and Sanders too old to be president? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/19/opinion/president-age-limit-biden.html

Castel, A. D. (2008). The adaptive and strategic use of memory by older adults: Evaluative processing and value-directed remembering. In A. S. Benjamin & B. H. Ross (Eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 48, pp. 225-270). London: Academic Press.

Castel, A. D. (2019a). Happiness: A funny thing happens as we get older. In Better with Age: The psychology of successful aging. Oxford University Press.

Castel, A. D. (2019b). Wisdom: The Benefits of Life Experiences and Creativity. In Better with Age: The Psychology of Successful Aging (pp. 63–80). Oxford University Press.

Gachter, S., Nosenzo, D., Renner, E., & Sefton, M. (2010). Who makes a good leader? Cooperativeness, optimism, and leading-by-example. Western Economic Association International, 953–967.

Grossmann, I., Jinkyung, N., Varnum, M. E., Park, D. C., Kitayama, S., & Nisbett, R. E. (2010). Reasoning about social conflicts improves with age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107.

Ling, P. (2020, February 3). Does history show that age affects US presidents’ performance? Plus, how old is too old? HistoryExtra. https://www.historyextra.com/period/modern /president-age-does-it-affect-performance-how-when-old-too-trump-sanders-biden/

McBride, D. M., Coane, J. H., Drwal, J., & LaRose, S. A. M. (2013). Differential effects of delay on time-based prospective memory in younger and older adults. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 700–721.

McGillivray, S., Friedman, M. C., & Castel, A. D. (2012). Impact of Aging on Thinking. In The Oxford handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 650–672).

Salthouse, T. (2010). Consequences of age-related cognitive declines. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 201–226.

Tentori, K., Osherson, D., Hasher, L., & May, C. (2001). Wisdom and aging: Irrational preferences in college students but not older adults. Cognition, 81, B87-96.