[Warning: The following post discusses key plot elements of the 2011 film Take Shelter. Although the post purposefully does not give away the ending, be advised that potential spoilers abound.]

Portrayals of schizophrenia in film go back to the earliest days of the medium. Throughout the past century, countless films have shown us individuals who are either in the process of losing touch with reality or are far past the breaking point. Charles Boyer famously drove Ingrid Bergman to the brink of madness in 1940’s Gaslight. Hitchcock gave us several iconic examples of delusional characters in masterpieces like Psycho and Vertigo. Jack Nicholson checked himself into an institution filled to the brim with men suffering from hallucinations and paranoia in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. And in the past 15 years, several biographical films have chronicled the lives of individuals who have been afflicted with schizophrenia, including David Helfgott (the Australian pianist portrayed by Geoffrey Rush in Shine), John Nash (the Nobel Laureate portrayed by Russell Crowe in A Beautiful Mind), and Nathaniel Ayers (the cello prodigy portrayed by Jamie Foxx in The Soloist). However, no film in recent memory has as disturbingly, accurately, or meticulously characterized the descent into psychosis as last fall’s overlooked gem Take Shelter.

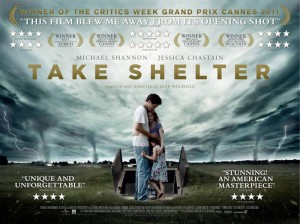

The film follows a man named Curtis LaFoche, a small town Ohio construction worker played by Michael Shannon (who received an Oscar nomination for his performance in 2008’s Revolutionary Road and currently co-stars on Martin Scorcese’s Emmy winning HBO drama Boardwalk Empire) and his beautiful wife, Samantha (portrayed by Jessica Chastain, who had an unparalleled breakthrough year starring in no less than six critically lauded films in 2011, including this, The Debt, Texas Killing Fields, Coriolanus, The Tree of Life, and The Help, for which she received an Oscar nomination). The couple is leading a fairly typical Midwestern life. They spend their time raising a young daughter, going to church, struggling with finances, and trying to please the in-laws. That’s at least how things appear from the outside. Internally, Curtis is engaged in the early stages of what will soon become a full-blown war.

It begins with apocalyptic visions of violent storms wreaking havoc on his home and community. These visions first appear to him in terrifying nightmares but quickly increase in frequency and intensity and – most troublingly – begin to affect his waking hours as well. His response to the visions is complex. On the one hand, he seeks out professional help, indicating that he knows what he is experiencing is not in sync with reality. He goes to see a counselor at a free clinic, who does exactly what a responsible counselor would do in this case – provide enormous empathy, gather a detailed psychiatric history, and refer to more appropriate help. Through meeting with this counselor, the viewer learns that Curtis’ mother is currently in an assisted living facility, having been diagnosed with schizophrenia at approximately the same age Curtis is now.

Despite this apparent insight, his delusional experiences prove too terrifying to truly discount. He starts devoting all of his time, energy, and savings to the renovation and elaboration of the storm shelter behind his family’s house, much to the shock and confusion of his wife and co-workers. He purchases gas masks for the family, he begins to lockout the dog (who became vicious in one of his nightmares), and he steadily distances himself from everyone in his life. His brother try to intervene, but is met with hostility. His irresponsible behavior incurs devastating repercussions, but he persists. Amidst all of this, his wife stays steadfast and supportive, doing all she can to reverse the decline. In one of the film’s most memorable scenes, she takes him to a community dinner where he is provoked into a terrifying rant, warning everyone that he will be the only one prepared for the storm that is about to come.

As art, the film succeeds spectacularly. As written and directed by newcomer Jeff Nichols, the film is taut, riveting, and realistic. The acting is superlative, with Shannon and Chastain giving masterful performances. The production values resemble those of a film made for 10 times its measly $5 million budget. It may have been overlooked by the Academy Awards in favor of films that were more heartwarming (Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, The Help, Moneyball) or made by more high profile filmmakers (The Tree of Life, Midnight in Paris, War Horse, Hugo), but many critics agreed that Take Shelter was among the very best films of 2011.

As a portrayal of a distinct phenomenon in clinical psychology, the film also succeeds remarkably well. It portrays mental health professionals as well intentioned, compassionate, and competent. It portrays hallucinations with stunning vividness, helping viewers understand why they are so difficult for individuals to distinguish from reality. And most notably, it accurately portrays the clinical phenomena at its core, prodromal schizophrenia.

As evidenced by the opening paragraph of this article, the experience of losing touch with reality has gone by countless names over the past century alone. Terms such as “insanity” and “madness” are outdated terms for the presently preferred construct of “psychosis,” a mental state characterized by symptoms that indicate impaired contact with reality. Such symptoms include “delusions” (a fixed false belief that is resistant to reason or confrontation with actual fact) and “hallucinations” (a sensory experience of something that does not exist outside the mind). Such symptoms can be found in several mental disorders, including severe mood disorders, substance use disorders, and personality disorders, but are most commonly associated with “schizophrenia.”

Schizophrenia is a severely impairing disorder that is characterized by a constellation of positive symptoms (such as delusions and hallucinations) and negative symptoms (such as lack of speech, motivation, or affect) that have been present for at least six months. It affects a portion of the population that is small relative to other disorders (0.3-0.7%), but is associated with profound suffering, health care utilization, social strife, and economic burden. Thus, research has long been interested in how the disorder can be detected early and possibly prevented. Much of this research has focused on the “prodrome,” the period of decreased functioning that is postulated to correlate with the onset of psychotic symptoms. A key aspect of the prodrome is that the individuals still retain some degree of insight into their symptoms. In other words, an individual in the prodrome is still somewhat able to see their symptoms as an aspect of an illness not as objective reality. Approximately one-third of individuals who meet current diagnostic threshold for the prodrome convert to schizophrenia (or a related disorder marked by psychotic features) within a few years. The work of researchers in this field, including those at UCLA’s Center for the Assessment and Prevention of Prodromal States, is rapidly evolving and immensely promising.

The film gets several aspects of the prodrome correct. The afflicted protagonist is male (males are approximately 1.4 times more likely to be diagnosed with psychosis than females), has a family history of schizophrenia (the heritability rate of schizophrenia is around 40%), and is rapidly deteriorating cognitively, emotionally, and socially despite retaining some degree of insight (as evidenced by the fact that he seeks out mental health services). The film not only gets the facts right, but the feelings, too. Curtis is living in abject terror, first of the fact that he might be losing grip with reality and later that doomsday is nigh. The film manages to exquisitely evoke the pain and fear of existing in the prodrome without exploiting it.

It should be noted that Shannon and Nichols have publicly stated the film is not about mental illness. To me, their comments seem more to highlight that the film is about larger and more ambiguous questions than “Is Curtis insane or not?” and with that I wholeheartedly agree. For me, the film is ultimately about gaining insight into a very human experience that most of us find perplexing and terrifying. Many of those who have seen the film (or hopefully will see the film after reading this article) will undoubtedly have doubts about the “twist” ending, which remarkably complicates both the narrative arc of the plot and the accuracy of the film’s portrayal of the mental illness at its center. I, for one, am still not sure what I think of the ending weeks after seeing it. What I do know, however, is that I have never looked at an individual telling me they are worried about whether or not what they are experiencing is in fact real the same way again.

[This is the 3rd post in Richard LeBeau’s series on Portrayals of Psychology in Film. Additional articles will be added in the coming weeks.

For past articles see: