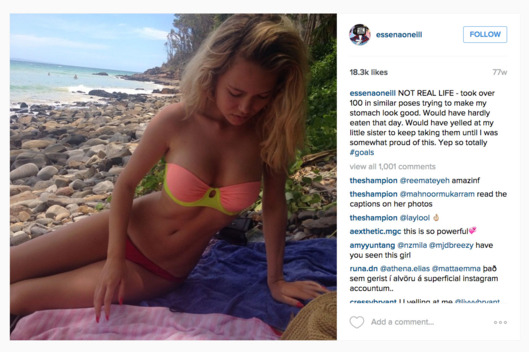

If you’ve been on social media in the past 48 hours, you may have seen one of several articles making the rounds about Essena O’Neill, the former teen Instagram model (yes, that’s a thing!) who gained popularity for her bikini-clad selfies and fitness tips. Essena made the decision to quit Instagram after growing disillusioned and unhappy with the staged nature of her social media presence. Before deleting her Instagram account, Essena recaptioned all of her photographs to reflect her true experiences when they were taken and posted. On one supposedly-candid image featuring Essena lounging on the beach, she wrote:

Essena’s story quickly went viral, and over the past couple of days has amassed hundreds of thousands of views across different news sites. Essena has been praised for exposing the true nature of many popular Instagram accounts — photographs that appear spontaneous and carefree are meticulously staged, and advertisers pay the popular users to wear their clothes and use their products. But while the medium is new, the issue to which Essena has drawn attention is a familiar one. Images of women in the media, particularly in advertisements, have long been the result of careful posing and lighting, digital filters and time-consuming and unhealthy approaches to exercise and diet. So often they are an idealized and unrealistic depiction the female form. Essena’s Instagram account is another example of misleading advertising, with the key difference being that many of her young fans did not know her account was a series of advertisements.

Reflecting on her experience, Essena wrote:

“I found myself drowning in the illusion. Social media isn’t real. It’s purely contrived mages and edited clips ranked against each other. It’s a system based on social approval, likes and dislikes, validation in views, success in followers… it’s perfectly orchestrated judgement. And it consumed me. “

Essena’s statement echoes something I often hear when discussing my work as a social media researcher with others: Is social media “real”? For Essena, it certainly wasn’t — her online image was a carefully cultivated version of herself, at great disconnect from her reality of grueling selfie shoots and paid endorsements. And for teens who feel a similar pressure to perform for likes, Instagram probably feels very far from genuine. Then again, even before social media, many adolescents felt the pressure to perform, to fit in, and to limit or change their self-expression in order to navigate their social world. But the Internet complicates the story. The quantifiable nature of social media – with likes, favorites, and followers displayed in numbers- can contribute to the disconnect between life on the screen and life in the ‘real world.’

For many adolescents, however, social media doesn’t always feel phony. In my research, I’ve spoken to teens about what they do on Instagram, what they like and dislike. Their answers suggest an experience somewhere between Essena’s performance and the ideal of the “genuine” self. Many of my participants have told me that they enjoy using Instagram to document their daily lives: activities, outings, and the people and things that make them happy. This documentation serves two purposes: teens can share their experiences with friends in real time, and they can keep a record of these memories for themselves, like a scrapbook of enjoyed activities both special and mundane. Teens say that Instagram pushes them to be creative and allows them to connect with others who share similar interests or artistic sensibility. Like Essena, however, some dislike that they or their friends feel a desire to project a particular image. And selfies, I’ve learned, are divisive among teens as well as adults!

Like the teens with whom I’ve spoken, many of Essena’s former followers probably felt that their own Instagram accounts reflected a genuine, if polished, self. And because of this, they perceived her account, with candid-looking pictures of a smiling teen and her daily life, as similarly genuine. Unlike a glossy magazine cover, which most teen girls could tell you has been Photoshopped extensively, Essena’s images were marketed as the real thing. She occupied the same space in the Instagram feed as teens’ close friends; her photos would literally pop up before or after a classmate or neighborhood friend. She posted the same kind of pictures: selfies, family, food, landscapes. This is precisely why Essena’s photographs feel, in retrospect, so insidious (and probably why advertisers were so eager to work with her).

Not only did she seem genuine to her followers, she appeared happy and healthy. Essena’s focus on her body was ostensibly a promotion of healthy lifestyle and activities, and she wasn’t the only Instagram celebrity selling this image. An immensely popular tag on Instagram is #fitspo, for short for “fit-spiration,” an amalgamation of “fitness” and “inspiration.” The tag is currently featured in 22.5 million+ posts on Instagram as of this blog post. Images tagged with #fitspo frequently feature selfies of individuals in activewear or bikinis, meant to inspire others to hit the gym, diet, and otherwise get in shape. When I began conducting social media research almost ten years ago, fitspo didn’t exist. Young women were more likely to encounter a different word online: “thinspo.” Thinspo was one of several shorthand terms used in the pro-anorexia community, which at that time existed across various message boards and blogging platforms. Community members posted dangerously thin models and actresses as a means of inspiring one another to cut calories and persevere in what they perceived to be a livable anorexic lifestyle. This was a fringe movement, but not so fringe that I didn’t discover it when I myself was a teen.

In 2015, #fitspo may not have the same associations with the pro-anorexia community (which has, I’ve observed, managed to perniciously reincarnate across each new social media platform) but it, too, promotes a dangerous idea. #Fitspo promotes an idealized and often unrealistic body type, but this time under the guise of inspiring healthy habits. Of course, physical fitness is not defined by six-pack abs on a sixteen-year-old or a thigh gap. But because #fitspo is not associated with an underground community promoting a serious eating disorder, and because of the reference to diet and exercise, it’s easier to forget about the potentially deleterious effects these images can have on self-esteem and behavior. Essena describes exercising for hours and severely depriving herself of food to achieve the body type that was lauded by her peers. What’s more, even with these efforts, it still took her hundreds of attempts to achieve a photograph that made her “somewhat proud.”

Research supports the notion that fitspo inspires young women to exercise, but with negative consequences for wellbeing. A recent paper published in the journal Body Image found that young women who viewed real Instagram images with the tag #fitspiration reported an increase in body dissatisfaction and negative feelings, as well as lower self-esteem (as compared to their ratings after viewing travel images). The experiment involved exposure to just 18 images during a single session. For Instagram users, photographs are continually streamed and accessed day after day. One can only hope that Essena’s viral story will inspire fans to look at these images differently, or even to reassess their goals and the accounts that they follow.

In the end, for all Essena has discussed quitting social media, she’s still a user: she has a new Vimeo account (replacing her previous popular Youtube account) and is using her website to connect with her fans and promote awareness of global issues. Of course, it would be unrealistic for a young woman in 2015, particularly one interested in spreading a social message, to quit social media. And we shouldn’t expect her to do so, for the same reason that the American Academy of Pediatrics recently revised their guidelines on media use for young children from “no media” to “limited media.” The Internet and social media have become completely integrated into the fabric of our daily lives. Quitting is an unrealistic long-term goal (although we can and should take breaks, especially when we fill our offline time with positive alternative activities). We DO have a choice, however, in how we endeavor to present ourselves to others, and what we choose to consume online (for more about this, check out Hannah’s great post).

Is social media “real”? It certainly has a very real effect on our daily interactions and how we feel about ourselves. Fortunately, many of the young people I’ve met use Instagram as a way to augment and facilitate their in-person social relationships. And that, to me, is quite #inspirational.