Babies are so much more capable than we give them credit for. The analogy that young children’s minds are like sponges overlooks the active role infants play in their development. But what tools are at their disposal that facilitates this active participation? Long before infants can walk or talk, they use vision as a key way to explore the world around them.

Even as adults, we often are more attentive to the things we look at and miss out on details that we ignore or don’t see. This inherently suggests a choice in what we attend to, regardless of whether it is conscious or not. Visual attention is one critical tool that infants can use to learn about things in their immediate environment. A large number of studies have elegantly shown how adept infants are at using vision to build an increasingly sophisticated understanding of the world. In particular, some studies have reported that the way infants selectively look at certain facial features (e.g., a person’s eyes versus their mouth) during different points in infancy supports specific aspects of social and communicative development. This is believed to be because eyes and mouths convey different types of information. The adage that the eyes are the windows of the soul highlights the rich social information they depict; whereas, a talking mouth provides a wealth of linguistic information. Therefore, paying attention to either the eyes or the mouth can support the uptake of social and communicative information. Understandably, a balance in looking to the eyes or the mouth is important for normative development.

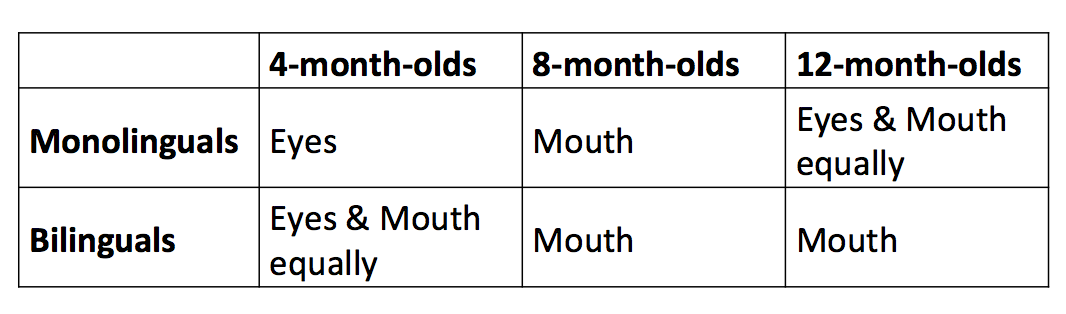

Something really interesting is that infants raised in monolingual versus bilingual households purportedly demonstrate different patterns of visual attention to talking faces. This appears especially evident between 6- to 12-months of age, which is around when infants start to make speech-like sounds and produce language themselves (e.g., babbling –> first word approximations). Studies have shown that infants from bilingual households persist in looking to the mouths of speakers past an age when infants from monolingual households do. This is hypothesized to help infants from bilingual households parse the multiple linguistic cues imparted to them. But how do these differences in looking patterns relate to actual language development?

Developmental trajectories in eye vs mouth looking in infants from monolingual vs bilingual households

This was a primary question in a recent study evaluating attention to facial features (e.g., mouths vs eyes) in 6- to 12-month-old infants from monolingual and bilingual households and its relation to their concurrent language skills. A secondary question this study examined was whether individual differences in attention to the mouth (vs the eyes) also affected aspects of social development, like discriminability of emotional expressions. The reason behind this second question was that if infants are more attentive to the mouth they might be missing relevant social cues from the eyes.

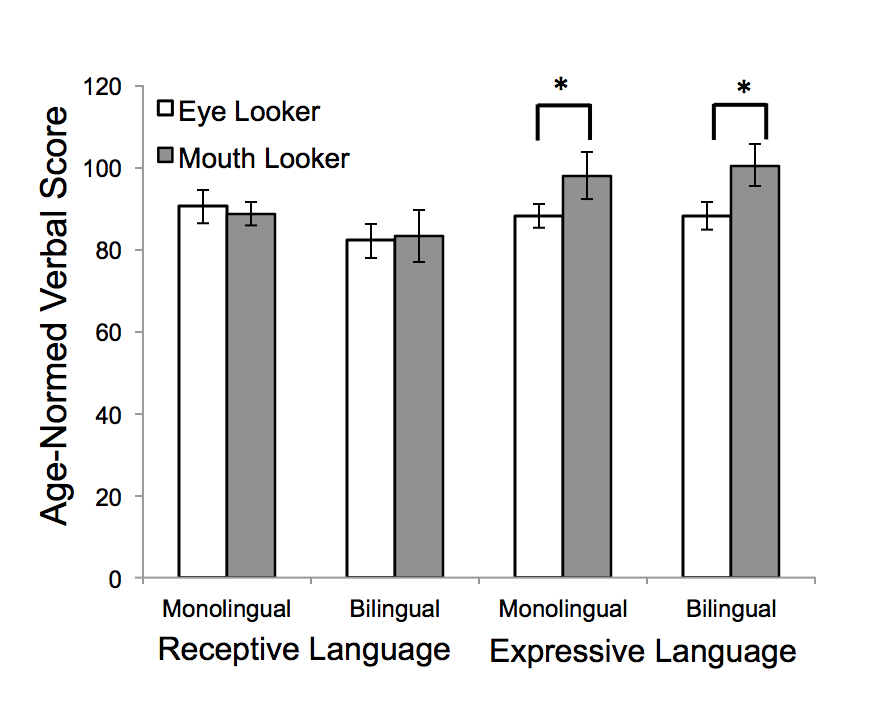

Tsang and colleagues found that attention to the mouth increased between 6- to 12-months of age in both monolingual and bilingual infants. Importantly, relative attention to the mouth was associated with language production skills (i.e., expressive language) but not language comprehension (i.e., receptive language). This was true in both monolingual and bilingual infants, which means that attention to the mouth is a general mechanism that supports language production. Moreover, relative attention to the mouth was more closely associated with language skill level than infant’s age, suggesting that we use age as a proxy measure of developmental skill level. Relative attention to the mouth was not associated with infants’ ability to discriminate emotional expressions, which means that attention to the mouth, and its association with language development, does not necessarily impede other aspects of social development.

6- to 12-month-old monolingual and bilingual infants who preferentially looked at the speaker’s mouth had higher age-normed expressive language skills than infants who preferentially looked at the eyes.

This is the first study to show that relative attention to the mouth during a period of rapid language learning directly supports budding skills in language production. The consistency between monolingual and bilingual infants is also telling because it suggests that mouth-looking may be a general mechanism that infants can use to get relevant linguistic signals from others.

The findings of this study are also really interesting to consider within the context of Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). There is some work showing that increased attention to the mouth in late toddlerhood may be particularly maladaptive for social cognitive development (however, in adults with ASD, mouth looking was a compensatory mechanism for better social functioning). This highlights the importance of developmental timing—the age of the individual and their developmental level—in understanding behavior. Certain behaviors are conducive for specific aspects of development at certain times. Given that, a noted caveat when reading about infant studies is that they shouldn’t be generalized across development. But that also makes infant research so exciting! Change is the constant and as infant researchers we are trying to figure out what those changes in behavior could mean for development.